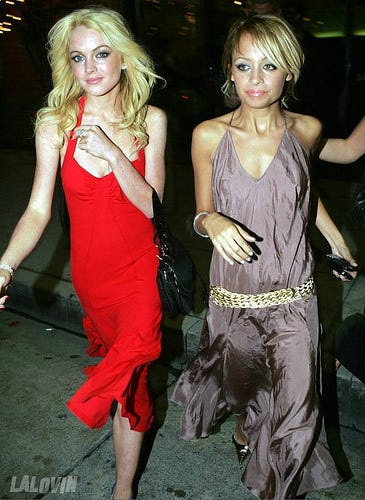

The early 2000s were a glitzy-glam, futuristic era of the flip phone, MTV, pencil-thin eyebrows and Juicy Couture. Pop icons like Paris Hilton, Britney Spears and Christina Aguilera dominated the media, with their incredibly slim physiques often photographed in daring, ‘go small or go home’ looks. But beneath the fun and rhinestones lay a dark truth that would stick with many of us even to this day – one where diet culture and ‘size zero’ would be glorified, pressuring women to mould their bodies into the tight confines of barely-there and size-exclusive styles that defined the era. As Y2K appears to be making a nostalgic comeback, so too does the conversation around Y2K diet culture and body image.

In this article, we dive into the defining trends of Y2K culture and how they became inextricably linked with impossibly narrow beauty standards, disordered eating and ‘fatphobia’ – and we ask ourselves, have we truly changed as a society?

What is Y2K and how did it define beauty standards at the time?

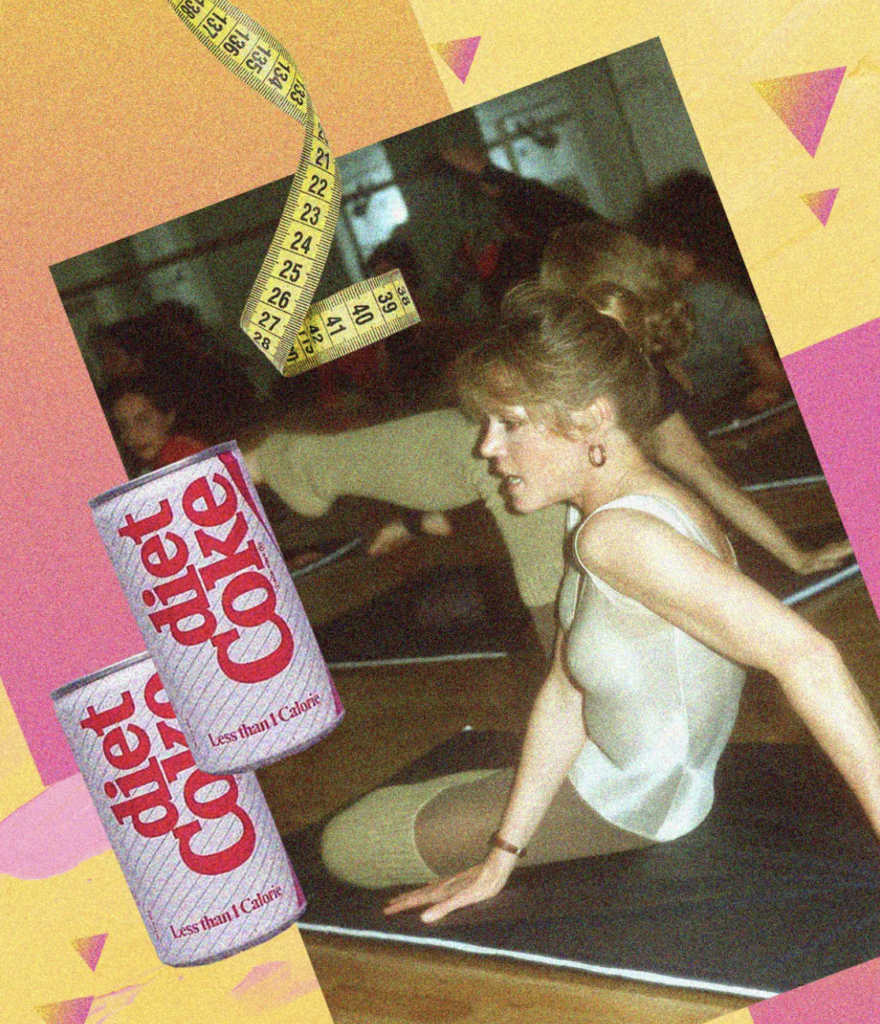

Y2K commonly refers to a distinct fashion aesthetic spanning the late 1990s and the early 2000s. It was the “wild child of the fashion family”: bold, experimental and rebellious, with a touch of “heroin-chic” carrying over from the mid-90s. Celebrities would often don pieces like midriff-baring baby tees, flirty micro mini-skirts and ultra low-rise jeans. The vibe was fun and futuristic, and the accessories were unapologetically gaudy.

However, as the trend gained traction with the public, something became strikingly apparent – the tightly fitted, awkward, skin-baring silhouettes enforced a clear message: Y2K was not for everyone. As Gianluca Russo, author of The Power of Plus: Inside Fashion’s Size-Inclusivity Revolution, says “Y2K style is largely grounded in thinness, [the] models’ bodies inevitably became an asset in nailing Y2K style”.

Youtuber Angela Benedict explained, in her video ‘Y2K Gave Me An Eating Disorder’, that to wear the clothes you were showcasing either your ribs or 6-pack abs. She described how the belly ‘pooch’ (a normal part of a woman’s body) would be exaggerated in certain styles, turning a “molehill” into a “mountain”. For Angela, the ‘Y2K mentality’ manifested itself into body dysmorphia, a hardcore regimented diet and exercise routine and laxatives abuse. Then, when she finally achieved a “freakishly thin” figure at 98 pounds (44kg) Angela recalls that she felt a disturbing sense of accomplishment. It didn’t help that her friends and family would praise her for her new body.

Now, this is something I can certainly relate to. As a slim and active kid in the early 2000s, I’d receive compliments for my body type. To be told “she could be a model!”, I probably felt a sense of validation and pride, and it reinforced the idea that a skinny body type was something to be admired. But little did I know that those seemingly innocuous remarks, though perhaps well-intentioned, would make me hyper-aware of my appearance from a young age. This would later evolve into years of struggling with obsessive and disordered eating behaviours, especially as I went through the physical changes of puberty.

Yet, I can’t help but acknowledge the pervasive cultural backdrop that normalised this idealisation of ‘skinny’. The message that “thinner is always better” was deeply entrenched in a whole generation of women’s minds because the influence was everywhere.

The role of tabloids, internet culture and media

When I was a kid, I vividly remember flipping through magazines at the doctor’s office being pretty much conditioned to believe that cellulite was the worst thing a woman could have. In those days, body positivity was non-existent. Toxic gossip magazines, like OK! and People, would often display dramatic before-and-after photos and listicles of ‘best and worst’ beach bodies. In fact, outright heinous remarks would be made to shame any celebrity who would dare to gain weight. Jessica Simpson was called “Jumbo Jessica” and mocked for “letting herself go”, and when Britney Spears performed at the 2007 MTV’s Video Music Awards (not long after the birth of her second child) E! Online wrote, ‘the bulging belly she was flaunting was SO not hot’ and a New York Post headline read ‘Lard and Clear’!

Fashion publications, like Cosmopolitan, Vogue and Elle, would also play a role in promoting the idea that being thin was the ultimate goal. Setting the agenda for what was considered beautiful, the front page would consistently feature ultra-thin models and celebrities who had “it” – the coveted “size zero” aesthetic. Like, in the same year, Mary-Kate Olsen was undergoing treatment for an unspecified eating disorder she featured on no less than four major magazine covers. The magazines would also contain an endless supply of fad diet routines and product advertisements, laying the foundation for what we now recognise as ‘diet culture’.

Beyond print media, the internet also became a breeding ground for toxic beauty standards. Remember the infamous saying “Nothing tastes as good as skinny feels”? Or the #thinspo and #proana (pro-anorexia nervosa) Tumblr content that glorified protruding bones, tiny waists and thigh gaps?

In movies, thin, conventionally attractive women were portrayed as lovable, successful and desirable as opposed to plus-sized women who were characterised as the “side kick”, used as comic relief or treated as tragic, slovenly and unworthy. From TV shows too, like The Biggest Loser and America’s Next Top Model, I’d fundamentally learnt “fat is bad, fat is failure” – a feeling I know today as internalised ‘fatphobia’. We were bombarded with images and quotes that reinforced the belief that being thin was not only attractive but also fashionable, superior and equivalent to health, worth and success.

So, have we changed as a society?

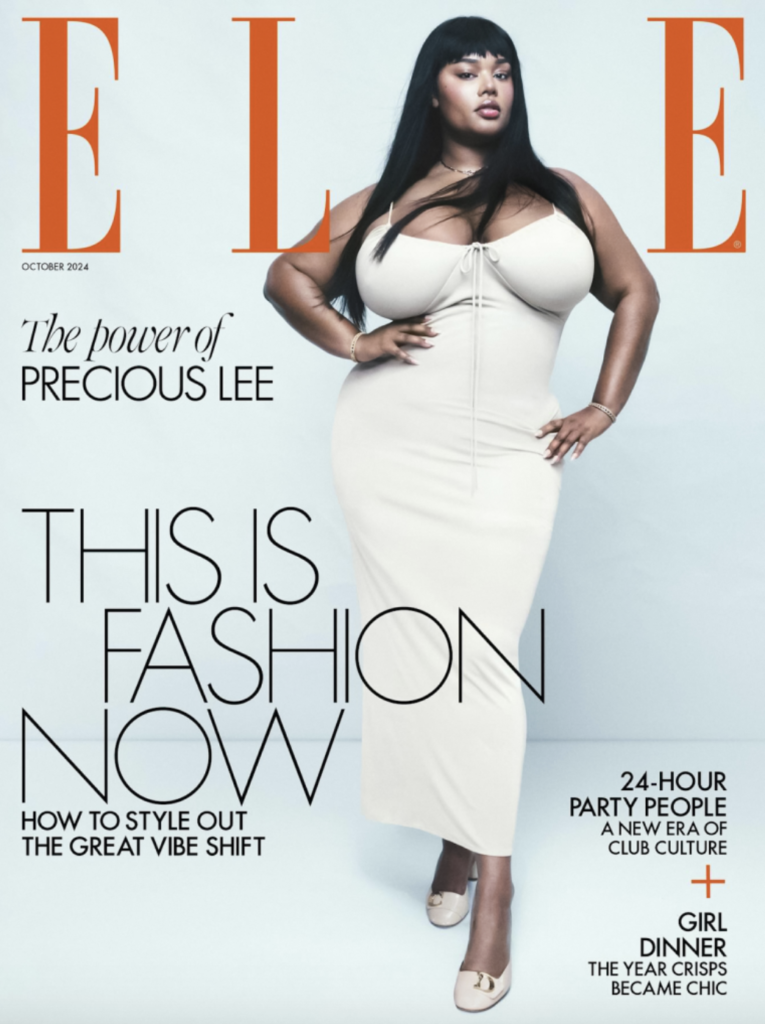

If today Perez Hilton were to make the same degrading bully/shame comments as he often did back then, I don’t think it would go by unnoticed. The same goes for fashion brands that don’t offer inclusive sizing. I recognise that perspectives have indeed shifted over the past decade. We’ve seen the rise of brands like Djerf Avenue and Savage x Fenty, which celebrate all body shapes, races, and gender identities as well as people with disabilities. Online, a new wave of plus-sized models and influencers have gained visibility and are leading the way in body positivity movements. Recently, Precious Lee graced the cover of Elle, and the iconic VS Fashion Show returned after a 6-year hiatus with models like Ashley Graham and Devyn Garcia included in the line-up. From a time when toxic messaging around thinness was openly and ruthlessly displayed, size inclusivity and body diversity are now a mainstream topic. So, when Y2K returned – beginning with that Miu Miu mini skirt – I wondered, have we moved away from the toxic, ‘skinny’-centric beauty standards of the early 2000s?

Unfortunately, it appears not. Despite the growing emphasis on body positivity, eating disorders are on the rise. Shockingly, an estimated 27% of young people under the age of 19 have an eating disorder – an increase of 12% since 2012.

A strong theory is that social media is to blame. While, yes, it has provided a space for advocating diversity and promoting confidence and self-acceptance it also perpetuates unrealistic beauty standards and fosters unhealthy comparisons. Influencers and celebrities frequently present a distorted and deceiving version of reality – through filters or being dishonest about cosmetic surgeries. Then, there are trends like ‘body checks’ and ‘what I eat in a day’ which subtly encourage self-scrutiny and, often, under-eating. I could keep going… but the crux of it, as I’m sure we’ve all repeatedly been told, is that social media can be incredibly detrimental, especially to the young and impressionable.

So, the problem remains. It just looks a little different.

But, the good news? You are not powerless. In a world still saturated with unrealistic ideals, you can control the messages you absorb. Start by:

- Diversifying your algorithm, and clicking ‘unfollow’ or ‘not interested’ when a creator or their content brings about negative feelings or self-talk;

- Taking regular breaks from social media to reset your mind (and dopamine!);

- Learning not to trust what you see online because many creators don’t show the whole truth – they carefully curate what you see.

And ultimately, instead of stressing over “body trends” or comparing yourself to impossible beauty ideals, remember to focus on what really matters:

living your one life fully in good health.

Read more of our Health & Wellness articles below.